Spare

Spars on Sailing Ships

“whaling vessels are the most exposed to accidents of all

kinds, and especially to the destruction and loss of the very things upon which

the success of the voyage most depends. Hence, the spare boats, spare spars,

and spare lines and harpoons, and spare everythings, almost, but a spare

Captain and duplicate ship.”

Herman Melville. Moby Dick. Chapter 20

Melville was focused on whaling ships because of the subject of his novel, and the very long, multi-year, voyages that whaling ships often undertook made spares critical for survival. Merchant sailing ships in the same time period, even though their voyages tended to be multiple months rather than multiple years long also carried a lot of spares. Many of the spares, such as spare rope, blocks and sails, would be stored below decks and thus would not be visible on a model of the ship. Spare spars were an exception. Spare spars were carried on top of deck houses, on frames between the bridge and foremast called gallows, and lashed to the sides or center of the main deck so they would be something that a modeler should be including in a model of a ship, such as a mid 1800s clipper ship. Note that, when I say “spare spars” I am including spare mast parts such as topmast and spare booms such as spare jib booms. There is one exception to this that I have found. The spare spars on the McKay ship Great Republic were carried below decks[i] which makes sense since her decks were mostly empty. But, in my viewing of many ship models I have found only a few that included spare spars. This article explores when such spare spars were carried on sailing ships and some details of how they were carried and what form they took to assist the modeler in deciding if spare spars should be included in a model, and, if so, what they should look like and where should they be located on the model. In this article I will be only discussing wooden spars and not iron ones.

I have been building a model of the Flying Cloud, the full rigged clipper ship built by Donald McKay in Boston and launched in 1851, so that is the class of ship I will focus on in this article. The oldest model of the Flying Cloud that I know of is the 1916 model built by the Horace E. Boucher Manufacturing Company and currently on display at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (MFA). This model includes a complement of spare spars. Specifically, what appears to be a spare main yard on the starboard side of the main deck and about 10 smaller spare yards on the roof of the main deck house. See figures 1 and 2. Due to the positioning of the model at the MFA, the port side of the deck cannot be viewed but, based on a model of the Flying Cloud made by Boucher in 1930 and now on display at the Addison Gallery at Phillips Academy, the model likely also includes a spare main topsail yard and a spare main topmast lashed to the port side of the deck.

figure 1 – MFA spare main yard figure 2 – MFA spare small yards

But, other than the two Boucher models, one other model of

the Flying Cloud on display at the San Francisco

Maritime Museum and a model of the William H. Webb clipper ship Challenge

in the Smithsonian Museum in Washington DC, I have not found any other models

showing spare spars, although I fully expect there are many that I have not

seen since I have seen only a few hundred models of sailing ships. In any case, it seems to be too rare

for modelmakers to include spare spars on their models of sailing ships. I have also not been able to locate any

paintings of sailing ships that included spare spars, which should have been

clearly visible on top of the main deck house. Maybe the artists did not consider spare spars worth

including.

That is not to say that it was rare for such ships to

include spare spars. Mention of

spare spars was very common in the literature about sailing of the day. To name just a few sources I have

found: Boyd, Manual for Naval Cadets 1857, page 232, Brady, The Kedge

Anchor, 1849 page 145, Chapman, All About Ships, 1869 – page

380, Dana, The Seaman’s Manual, 1841 page 77, Dana, Two Years Before

the Mast, 1840 page 347, Fordyce, Outlines of Navel Routine, 1837

page 3, Luce, Seamanship, 1863 page 319-320, Scammon, List of Stores and Outfits for a First-Class

Whale-Ship, 1874 page 6, and Totten,

Naval Text Book, 1841 page 123.

(All of these are available for download on the web.)

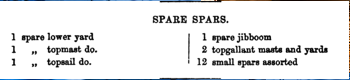

Most of these books, as well as the dozen or so others I found mention of spare spars in, did not say much about the spars themselves. The tone of the books was that all significant ships carried spare spars and that spare spars were not exceptional. The books described using spare spars to build rafts or rudders in cases of emergency, spare spars being washed overboard in gales, or said, almost in passing, that ships did carry spare spars. Sometimes the books said where the spars were located, but they did not go into much detail about just which spars were included. There was one exception I found - Chapman’s 1869 All About Ships which provides a table of what spares would have been carried on a China Clipper of 1869. See figure 3.

Figure 3 – Chapman All About Ships page 380

Totten’s Naval Text Book provides a more general list of spare spars that would be present on a warship in the mid 1800s. He focuses on how the spars should be stored and labeled rather than providing a clear table of which sparts should be included.

In addition to the large number of contemporary books mentioning spare spars in one context or another, I found a quite a number of old photographs showing spare spars on ships.

See figures 4 to 7 for examples.

figure 4 Glory of the Seas

figure 5 – unknown ship in LA 1905

Figure 6 – unknown ship in New York Figure 7 - Martha Davis in Boston

It seems clear from all documents and photographs that spare spars were common, if not ubiquitous, on sailing ships in the 1800s, at least those sailing ships that undertook long voyages.

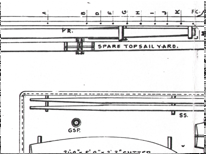

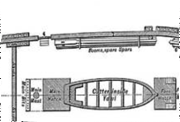

Since they were so common, it would make sense, at least to me, that spare spars should appear on ship modeling plans, but I have not found that to be the case. Even Boucher’s own plans of the Flying Cloud, drawn in 1928, do not include spare spars. In looking at hundreds of plans I have only found two, a set of 1832 plans for the HMS Beagle and a 1933 set of plans for the Flying Cloud drawn by W.A. White, that include spare spars. The spare spars on the White plans are consistent with the spare spars on the Boucher model in the MFA. White may have known of the model and simply followed its lead in drafting his plans. See figures 8 and 9.

Figure 8 – detail of W.A. White plans Figure 9 detail of Beagle plans

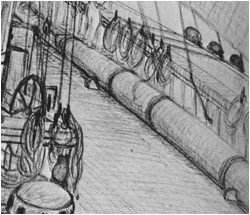

Another question I tried to resolve: how much hardware should be on these spare spars? The larger wooden yards on sailing ships used forged iron bands to keep them together and to provide mounting points for blocks. It would seem to make sense to fit these bands to the spare spars on shore so that the spare spar would be ready to use when needed and to avoid having the kind of far too dangerous forge needed on an all too flammable ship. The few photographs that I have found that show the larger yards lashed to decks support this idea as does a drawing done in 1880 by a passenger on a ship named the Ice King. See figure 10 (from a sketchbook in the Peabody Essex Museum).

Figure 10 – detail of a drawing by Marina L. Sargent

But, as can be seen in figure 1, the Boucher models of the Flying Cloud do not include any hardware, other than the sheave for the sheet chain on the spare lower yard.

The lessons from the photographs and documents concerning

the smaller spars are not as definitive. For example, figures 4 and 5 show

bands on the smaller spars but figure 7 does not. Some of the documents, such as Totten’s

Naval Text Book, say that some specific spare yards, the topsail yards

for example, “should be as completely rigged as possible.” But Totten

and most of the other documents are silent as to the hardware on the smaller

spare yards. Examining the

photographs that show the spare spars closely indicates that many of the spare

spars were finished to the point of having iron bands, the yard ends formed and

at least the mortices cut for the sheet chains and ropes, they may have also

had the sheaves installed as well. The smaller spare spars in the

photographs did not have their ends shaped, nor did they have bands or the sheet

mortices cut.

None of the photographs I

have found show jackstays installed in the spare spars. Also, none of the photographs show the yard

arm band (the band at the end of the yard where the yard braces terminate)

installed on the spares. This

makes sense since yard arm bands in various standard sizes could be stocked and

installed as needed and having the bands on the spars would make them harder to

handle and the arm bands are relatively fragile. The same is true for the inner and outer studding sail boom

irons.

Spars, other than the lower

yards, which used trusses, are attached to the masts using wooden battens. I have found no photographs that show

spare spars with battens attached.

But if you look closely at the top left corner of figure 10, it looks

like there might be a truss attached to the spare main yard.

As can be seen in figures 6

and 7, the large spars on the deck were supported by chocks. Figure 6 also shows a large spare spar

lashed to the chocks to keep it in place in case of rough seas.

Figures 4, 5 and 7 above

show smaller spare spars lashed to beams placed on top of the main deck house,

but figure 11 below shows what may have been the case in too many ships, a

disordered pile of spare spars, ladders and gangplanks between the boats on top

of the main deck house.

Figure 11 Sea Witch in Boston

Spars on sailing ships in the 1800s were left natural on some ships and painted white or black on other ships. I did find one photograph that showed a large spare spar or spare topmast painted black but in all other cases, the photographs seem to show unpainted spars.

For my model of the Flying Cloud I have decided to follow Chapman’s list (which is consistent with the Boucher models and the White plans when it comes to the large spares) and include a spare main lower yard lashed on the starboard side of the deck next to the waterway, a spare main topsail yard and a spare main topmast, both lashed on the port side of the deck near the waterway. In addition, I will include a spare jibboom, two spare main topgallant yards and main topgallant masts as well as a dozen smaller spare yards of various lengths from the size of a main skysail yard to the size of main lower yard studding sail boom, all lashed to the top of the main deck house. I will include shape the ends and include iron bands on all but the smallest of the spare spars. Finally, since other research indicates that the yards on the Flying Cloud were painted black while the booms, gaffs and upper masts were left natural, and the lower masts along with the tops were painted white, I will follow that color scheme for the spares.